How Does Church Government Work?

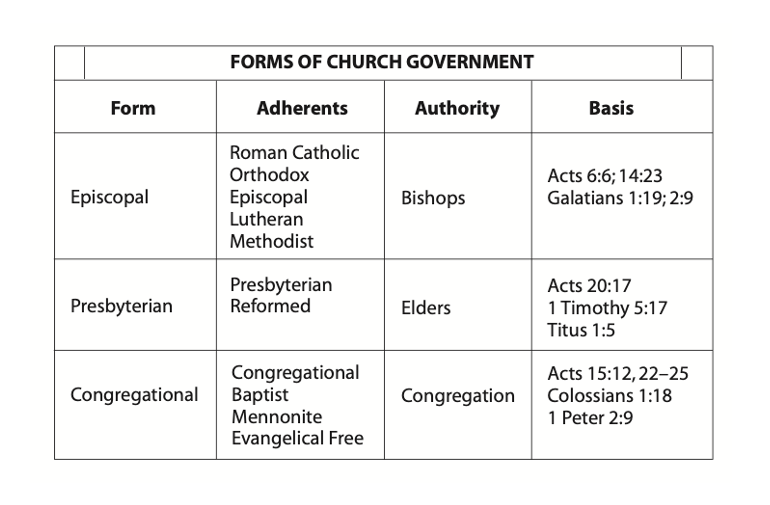

The church as the body of Christ is a living organism, analogous to the human body with the head giving it direction, even as Christ is the head of the church, giving it direction. Nonetheless, there is also organization that governs the functioning of the church. Historically, three different types of church government have emerged.

Types of Church Government

Episcopal

The name episcopal comes from the Greek word episkopos, meaning “overseer” (the word is also translated “bishop” in the KJV), and identifies churches governed by the authority of bishops. Different denominations are identified by episcopal government, the simplest form being the Methodist church. More complex structure is found in the Episcopal (Anglican) church. The most complex episcopal structure is found in the Roman Catholic Church, with the ultimate authority vested in the bishop of Rome, the pope.[1] The Lutheran church also follows the episcopal form.

In the episcopal form of church government the authority rests with the bishops who oversee not one church, but a group of churches. Inherent in the office of bishop is the power to ordain ministers or priests. Roman Catholics suggest this authority is derived through apostolic succession from the original apostles. They claim this authority on the basis of Matthew 16:18–19. Others, such as the Methodists, do not acknowledge authority through apostolic succession.

“The church as the body of Christ is a living organism.”

This form of government arose in the second century, but adherents would claim biblical support from the position of James in the church of Jerusalem, as well as the position and authority of Timothy and Titus.

Presbyterian

The name presbyterian comes from the Greek word presuteros, meaning “elder,” and suggests the dignity, maturity, and age of the church leaders. Presbyterian (sometimes termed federal) designates a church government that is governed by elders as in the Presbyterian and Reformed churches. In contrast to the congregational form of government, the presbyterian form emphasizes representative rule by the elders who are appointed or elected by the people. The session, which is made up of elected ruling elders (the teaching elder presiding over it), governs the local church. Above the session is the presbytery, including all ordained ministers or teaching elders as well as one ruling elder from each local congregation in a district.[2] “Above the presbytery is the synod, and over the synod is the general assembly, the highest court. Both of these bodies are also equally divided between ministers and laymen or ruling elders.”29 The pastor serves as one of the elders.

The biblical support for this is the frequent mention of elders in the New Testament: there were elders in Jerusalem (Acts 11:30; 15:2, 4) and in Ephesus (Acts 20:17); elders were appointed in every church (Acts 14:23; Titus 1:5); elders were responsible to feed the flock (1 Peter 5:1, 2); there were also elders who ruled (1 Tim. 5:17).

Congregational

In congregational church government the authority rests not with a representative individual but with the entire local congregation. Two things are stressed in a congregational governed church: autonomy and democracy.30 A congregational church is autonomous in that no authority outside of the local church has any power over the local church. In addition, congregational churches are democratic in their government; all the members of the local congregation make the decisions that guide and govern the church. This is particularly argued from the standpoint of the priesthood of all believers. Baptists, Evangelical Free, Congregational, some Lutherans, and some independent churches follow the congregational form of church government.

The biblical support for congregational church government is that the congregation was involved in electing the deacons (Acts 6:3–5) and elders (Acts 14:23)31; the entire church sent out Barnabas (Acts 11:22) and Titus (2 Cor. 8:19) and received Paul and Barnabas (Acts 14:27; 15:4); the entire church was involved in the decisions concerning circumcision (Acts 15:25); discipline was carried out by the entire church (1 Cor. 5:12; 2 Cor. 2:6–7; 2 Thess. 3:14); all believers are responsible for correct doctrine by testing the spirits (1 John 4:1), which they are able to do since they have the anointing (1 John 2:20).

Evaluation of Church Government

In evaluating the three forms of church government, the episcopal form is based partly on the authority of the apostles, which really does not have a counterpart in the New Testament church beyond the apostolic era. Christ had given a unique authority to the Twelve (Luke 9:1) that cannot be claimed by any person or group, nor is there a biblical basis for any form of apostolic succession. The authority Jesus gave to Peter (Matt. 16:18–19) was given to all the apostles (Matt. 18:18; John 20:23) but to no successive group. The episcopal form of church government can be seen in the second century but not in the first.

The presbyterian form of church government has strong support for its view of the plurality of the elders; there are many New Testament examples. The New Testament, however, reveals no organization beyond the local church.

The congregational form of church government finds biblical support for all the people being involved in the decision making of the church. It can safely be said that elements of both the presbyterian and congregational forms of church government find support in Scripture.

[1] Erickson, Christian Theology, 3:1070.

[2] Saucy, The Church in God’s Program, 112.

The Moody Handbook of Theology

by Paul Enns

The study of God, His nature, and His Word are all essential to the Christian faith. Now those interested in Christian theology have a newly...

Free ebook: Habits for Spiritual Growth

Sign up for our weekly email and get a free download

Bible Insights by Email

Sign up for learning delivered to your inbox weekly

Free ebook: Habits for Spiritual Growth

Sign up for our weekly email and get a free download