What Are the Gifts of the Holy Spirit?

Definition of the Gifts

There are two Greek words generally used to describe spiritual gifts. The first is pneumatikos, meaning “spiritual things” or “things pertaining to the spirit.” This word emphasizes the spiritual nature and origin of spiritual gifts; they are not natural talents but rather have their origin with the Holy Spirit. They are supernaturally given to a believer by the Holy Spirit (1 Cor. 12:11).

The other word often used to identify spiritual gifts is charisma, meaning “grace gift.” The word charisma emphasizes that a spiritual gift is a gift of God’s grace; it is not a naturally developed ability but rather a gift bestowed on a believer (1 Cor. 12:4). This emphasis is seen in Romans 12 where Paul discusses spiritual gifts. He stresses that spiritual gifts are received through the “grace given” to believers (Rom. 12:3, 6).

A concise definition of spiritual gifts is simply a “grace gift.” A more complete definition is “a divine endowment of a special ability for service upon a member of the body of Christ.”[1]

Explanation of the Gifts

Two concepts are involved in spiritual gifts. First, a spiritual gift to an individual is God’s enablement for personal spiritual service (1 Cor. 12:11). Second, a spiritual gift to the church is a person uniquely equipped for the church’s edification and maturation (Eph. 4:11–13).

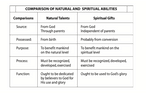

It should also be noted what is not meant by spiritual gifts.[2] It does not mean a place of service. Some may suggest, “He has a real gift for working in the slums.” This, of course, is a wrong concept of spiritual gifts. Nor is a spiritual gift an age group ministry. Or some might say that “he has a real gift for working with senior highs.” A spiritual gift is not the same as a natural talent; there may be a relationship, but a natural talent is an ability that a person may have from birth and develop, whereas a spiritual gift is given supernaturally by God at the moment of conversion. Natural talents and gifts may be contrasted thus:[3]

Description of the Gifts

Apostle (Eph. 4:11)

An important distinction must be made between the gift and the office of the apostle. The office of apostle was limited to the Twelve and to Paul. In Luke 6:13 Jesus called the disciples to Himself and chose twelve of them “whom He also named as apostles.” To those twelve Jesus gave a unique authority that was limited to those holding the office of apostle (cf. Luke 9:1; Matt. 10:1). Later, in defending his own apostleship, Paul emphasized that the signs of a true apostle were performed by him (2 Cor. 12:12). The qualifications for the office of apostle are set forth in Acts 1:21–22; those holding the office had to have walked with the Lord from the baptism of John until the ascension of Christ. Paul’s situation was unique; he referred to himself as an apostle but one “untimely born” (1 Cor. 15:8–9).

The gift of apostle is mentioned in 1 Corinthians 12:28 and also Ephesians 4:11. The word apostle comes from apo, meaning “from,” and stello, meaning “to send.” Hence, an apostle is one that is “sent from.” It appears the word was used in a technical sense as well as a general sense. In a technical sense it was limited to the Twelve who had the office of apostle as well as the gift.[4] In that sense it was a foundational gift limited to the formation of the church (Eph. 2:20). When the foundation of the church was laid, the need for the gift ceased. Just as the office of apostle has ceased (because no one can meet the qualifications of Acts 1:21–22), so the gift of apostle in the strict sense has ceased. The word apostle is also used in a general sense of a “messenger” or a “sent one” in the cause of Christ. These are referred to as apostles but do not have either office or gift. The word is used in a nontechnical sense of one who is a messenger (cf. Acts 14:14; 2 Cor. 8:23; Phil. 2:25).

The term “apostle” may be summarized as follows:[5] (1) Apostles were representatives of Christ (Matt. 10:1–15) who had authority in the early church (Acts 15:4, 6, 22, 23). (2) Apostles performed signs, wonders, and miracles (2 Cor. 12:12). (3) Apostles were witnesses of the resurrected Lord (1 Cor. 9:1–2; 15:5–8). (4) Apostles were given to the church only at the beginning (Eph. 2:20). (5) Apostles received direct revelation from the Lord (Gal. 1:12). (6) Apostles were not expected after Paul (1 Cor. 15:8).

Prophet (Rom. 12:6)

The lexical meaning of prophesy (propheteuo) means: (1) proclaim a divine revelation; (2) prophetically reveal what is hidden; (3) foretell the future.[6] There are many clear examples showing prophesy means foretelling the future. There is no clear reference showing prophesy is used as a synonym for teaching, i.e., “forthtelling” God’s truth.

The gift of prophecy is mentioned in Romans 12:6, 1 Corinthians 12:10, and Ephesians 4:11. The apostle received his information through direct revelation from God; hence, Agabus announced the famine that would come over the world (Acts 11:28) and Paul’s captivity in Jerusalem (Acts 21:10–11). Through direct revelation the prophet received knowledge of divine “mysteries” (1 Cor. 13:2) that man would not otherwise know. Prior to the completion of the canon the gift of prophecy was important for the edification of the church (1 Cor. 14:3). The prophet received direct revelation from God and taught the people for their edification, exhortation, and consolation (1 Cor. 14:3). Since the revelation came from God, it was true; the genuineness of the prophet was exhibited in the accuracy of the prophecy (cf. Deut. 18:20, 22). Prophecy thus involved foretelling future events. The gift of prophecy is also related to the foundation of the church (Eph. 2:20). Because the foundation of the church has been laid and the canon of Scripture is complete there is no need for the gift of prophecy.

Miracles (1 Cor. 12:10)

The nature of biblical miracles is a large subject, and the student is encouraged to study this as a separate topic.[7] Miracles did not happen at random throughout Scripture but occurred in three major periods: in the days of Moses and Joshua, Elijah and Elisha, and Christ and the apostles. There were select miracles outside that scope of time, but not many. Miracles were given to authenticate a message, and in each of the above-mentioned periods, God enabled His messengers to perform unusual miracles to substantiate the new message they were giving. Miracles occurred in the New Testament era to validate the new message the apostles preached. With the completion of the canon of Scripture the need for miracles as a validating sign disappeared; the authority of the Word of God was sufficient to validate the messenger’s word.

The gift of miracles (1 Cor. 12:10, 28) is a broader gift than the gift of healing. The word miracles means “power” or “a work of power.” Examples of the exercise of miracles are Peter’s judging of Ananias and Sapphira (Acts 5:9–11) and Paul judging Elymas the magician with blindness (Acts 13:8–11).[8] The word is also used to describe the miracles of Christ (Matt. 11:20, 21, 23; 13:54).

A distinction should be made between miracles and the gift of miracles. Although the gift of miracles—the ability of an individual to perform miraculous acts—ceased with the apostolic age, that is not to say miracles cannot and do not occur today. God may directly answer the prayer of a believer and perform a miracle in his life. God may heal a terminally ill person in answer to prayer, but He does not do it through a person’s gift of miracles.

Healing (1 Cor. 12:9)

A narrower aspect of the gift of miracles is the gift of healing (1 Cor. 12:9, 28, 30). The word is used in the plural (Gk. iamaton, “healings”) in 1 Corinthians 12:9, suggesting “the different classes of sicknesses to be healed.”[9] The gift of healing involved the ability of a person to cure other persons of all forms of sicknesses. An examination of New Testament healings by Christ and the apostles is noteworthy. These healings were:[10] instantaneous (Mark 1:42); complete (Matt. 14:36); permanent (Matt. 14:36); limited (constitutional diseases [e.g., leprosy, Mark 1:40], not psychological illnesses); unconditional (including unbelievers who exercised no faith and did not even know who Jesus was [ John 9:25]); purposeful (not just for the purpose of relieving people from their suffering and sickness. If this were so, it would have been cruel and immoral for our Lord to leave the cities, where the sick sought healing, for the solitude of the country [Luke 5:15, 16]); subordinate (secondary to preaching the Word of God [Luke 9:6]); significant (intended to confirm Him and the apostles as the messengers of God and their message as a Word from God [ John 3:2; Acts 2:22; Heb. 2:3, 4]); successful (except in the one case where the disciples’ lack of faith was the cause of failure [Matt. 17:20]); and inclusive (the supreme demonstration of this gift was in raising the dead [Mark 5:39–43; Luke 7:14; John 11:44; Acts 9:40]).

A distinction should be made between the gift of healing and healing itself. As in the case of the other sign gifts, the gift of healing terminated with the completion of the canon of Scripture; there was no further need for the gift of healing. However, God may still respond to the prayers of His children and heal a person of illness; this is, however, without the agency of another person. God may heal a person directly. A distinction between these two forms of healing appears to be the case in Acts 9, where Peter heals Aeneas through the gift (Acts 9:34) but God heals Tabitha in response to the prayer of Peter (Acts 9:40).[11]

It should also be noted that there are a number of examples where God chose not to heal people (2 Cor. 12:8–9; 1 Tim. 5:23).

Tongues (1 Cor. 12:28)

A number of observations help to clarify the meaning of this gift. (1) The book of Acts establishes that biblical tongues were languages (Acts 2:6, 8,11). When the foreign Jews visited Jerusalem at Pentecost they heard the apostles proclaim the gospel in their native languages (cf. vv. 8–11).

Tongues of Acts and Corinthians were the same. There is no evidence that the tongues of Corinthians were different from the ones in Acts or that they were angelic languages (1 Cor. 13:1).[12]

Tongues were a lesser gift (1 Cor. 12:28). The foundational gifts that were given for the upbuilding of the church were apostle, prophet, evangelist, pastor-teacher, and teacher (1 Cor. 12:28; Eph. 4:11). Tongues were mentioned last to indicate they were not a primary or foundational gift (1 Cor. 12:28).

Tongues were a temporary sign gift (1 Cor. 13:8). The phrase “they will cease” is in the middle voice, emphasizing “they will stop themselves.” The implication is that tongues would not continue until “the perfect comes”— the time when knowledge and prophecy gifts would be terminated—but would cease of their own accord when their usefulness terminated. If tongues were to continue until “the perfect comes,” the verb would likely be passive in form.

Tongues were a part of the miraculous era of Christ and the apostles and were necessary, along with the gift of miracles, as an authenticating sign of the apostles (2 Cor. 12:12). With the completion of the Scriptures there was no longer any need for an authenticating sign; the Bible was now the authority in verifying the message that God’s servants proclaimed. Tongues were a sign gift belonging to the infancy stage of the church (1 Cor. 13:10–11; 14:20).

Tongues were used as a sign to unbelieving Jews and in this sense were used in evangelism (1 Cor. 14:21–22). When unbelieving Jews would enter the assembly and hear people speaking in foreign languages it was a sign to them that God was doing a work in their midst, reminiscent of Isaiah’s day (Isa. 28:11–12). This sign should lead them to faith in Jesus as their Messiah.

Interpretation of tongues (1 Cor. 12:10)

The gift of interpretation of tongues involved the supernatural ability of someone in the assembly to interpret the foreign language spoken by one who had the gift of tongues. The language would be translated into the vernacular for the people who were present.

Evangelism (Eph. 4:11)

The word euanggelistas, written in English as evangelists, means “one who proclaims the good news.” One definition of the gift of evangelism is “the gift of proclaiming the Good News of salvation effectively so that people respond to the claims of Christ in conversion and in discipleship.”[13]

Several things are involved in the gift of evangelism:[14] (1) It involves a burden for the lost. The one having this gift has a great desire to see people saved. (2) It involves proclaiming the good news. The evangelist is one who proclaims the good news. While men such as Billy Graham undoubtedly have the gift of evangelism, it is not necessary to limit the gift to mass evangelism. An evangelist will also share the good news with unbelievers on a one-to-one basis. (3) It involves a clear presentation of the gospel. The evangelist has the ability to present the gospel in a simple and lucid fashion; he proclaims the basic needs of salvation—sin, the substitutionary death of Christ, faith, forgiveness, reconciliation—in a way that unbelievers without a biblical background can understand the gospel. (4) It involves a response to the proclamation of the gospel. The one having the gift of evangelism sees a response to the presentation of the gospel; that is an indication he has the gift. (5) It involves a delight in seeing people come to Christ. Because it is his burden and passion, the evangelist rejoices as men and women come to faith in Christ.

Although only some people have the gift of evangelism, other believers are not exempt from proclaiming the good news. All believers are to do the work of evangelism (2 Tim. 4:5).

Pastor-teacher (Eph. 4:11)

One gift is in view in the statement of Ephesians 4:11, not two gifts. The word pastor (Gk. poimenas) literally means “shepherd” and is used only here of a gift. It is, however, used also of Christ who is the Good Shepherd (John 10:11, 14, 16; Heb. 13:20; 1 Peter 2:25) and designates the spiritual shepherding work of one who is a pastor-teacher. The work of a pastor has a clear analogy to the work of the shepherd in caring for his sheep. “As a pastor, he cares for the flock. He guides, guards, protects, and provides for those under his oversight.”[15] An example is found in Acts 20:28 where Paul exhorts the elders from Ephesus “to shepherd the church of God.” It is to be done voluntarily, not for material gain nor by lording it over believers but rather by being examples of humility (1 Peter 5:2–5).

There is a second aspect to this gift; it involves the ability to teach. It is sometimes said of a church pastor: “He can’t teach very well, but he is a fine pastor.” That, of course, is impossible. If a person has this gift he is both a shepherd and a teacher. “As a teacher, the emphasis is on the method by which the shepherd does his work. He guides, he guards, he protects by teaching.”[16] This is an important emphasis for the maturation of believers in a local church. Paul strongly exhorted Timothy to faithfulness in teaching the Word (1 Tim. 1:3, 5; 4:11; 6:2, 17).

There are several related terms. Elder (Titus 1:5) denotes the dignity of the office; overseer designates the function or the work of the elder (1 Tim. 3:2)—it is the work of shepherding; pastor denotes the gift and also emphasizes the work as a shepherd and teacher.

Teacher (Rom. 12:7; 1 Cor. 12:28)

A pastor is also a teacher, but a teacher is not necessarily also a pastor. A number of factors would show that a person has the gift of teacher. He would have a great interest in the Word of God and would commit himself to disciplined study of the Word. He would have an ability to communicate the Word of God clearly and apply the Word to the lives of the people. This gift is clearly evidenced in a man who has the ability to take profound biblical and theological truths and communicate them in a lucid way so ordinary people can readily grasp them. That is the gift of teaching. This gift was emphasized considerably in the local churches in the New Testament because of its importance in bringing believers to maturity (cf. Acts 2:42; 4:2; 5:42; 11:26; 13:1; 15:35; 18:11, etc.).

Two things should be noted concerning the gift of teaching. First, it requires development. A person may have the gift of teaching, but for the effective use of the gift it would demand serious study and the faithful exercise of the gift. Second, teaching is not the same as a natural talent. Frequently public school teachers are given positions of teaching in a local church. It does not necessarily follow that their natural ability to teach means they have the spiritual gift of teaching. The natural ability and the spiritual gift of teaching are not the same.

Service (Rom. 12:7)

The word service (Gk. diakonia) is a general word for ministering or serving others. The word is used in a broad sense and refers to ministry and service to others in a general way. A sampling of the usages of this word indicates that: Timothy and Erastus served Paul in Ephesus (Acts 19:22); Paul served the Jerusalem believers by bringing them a monetary gift (Rom. 15:25); Onesiphorus served at Ephesus (2 Tim. 1:18); Onesimus was helpful to Paul while he was in prison (Philem. 13); the Hebrew believers displayed acts of kindness (Heb. 6:10). From these and other examples, it appears an important aspect of serving is helping other believers who are in physical need. This gift would be less conspicuous, with the believer serving others in the privacy of a one-to-one relationship.

Helps (1 Cor. 12:28)

The word helps (Gk. antilempsis) denotes “helpful deeds, assistance. The basic meaning of the word is an undertaking on behalf of another.”[17] The word is similar to serving, and some see these gifts as identical. Certainly they are quite similar if not the same. The word occurs only here in the New Testament, but the related Greek word, antilambanesthai, occurs in Luke 1:54; Acts 20:35; 1 Timothy 6:2. The gift of helps means “to take firm hold of someone, in order to help. These ‘helpings’ therefore probably refer to the succoring of those in need, whether poor, sick, widows, orphans, strangers, travellers, or what not.”[18]

Faith (1 Cor. 12:9)

While all Christians have saving faith (Eph. 2:8) and should exhibit faith to sustain them in their spiritual walk (Heb. 11), the gift of faith is possessed by only some believers. “The gift of faith is the faith which manifests itself in unusual deeds of trust. . . . This person has the capacity to see something that needs to be done and to believe God will do it through him even though it looks impossible.”[19] Stephen exhibited this gift, as he was “a man full of faith” (Acts 6:5). Men such as George Mueller and Hudson Taylor are outstanding examples of those possessing the gift of faith.[20]

Exhortation (Rom. 12:8)

The word exhortation (Gk. parakalon) means “called alongside to help.” The noun form is used of the Holy Spirit as the believer’s helper (John 14:16, 26). “The exhorter is one who has the ability to appeal to the will of the individual to get him to act.”[21] The gift of exhortation is “often coupled with teaching (cf. 1 Tim. 4:13; 6:2), and is addressed to the conscience and to the heart.”[22]

The gift of exhortation may be either exhortation, urging someone to pursue a particular course of conduct (cf. Jude 3), or it may be consolation or comfort in view of someone’s trial or tragedy (Acts 4:36; 9:27; 15:39).[23]

Discerning spirits (1 Cor. 12:10)

In the early church, before the canon of Scripture was complete, God gave direct revelation to individuals who would communicate that revelation to the church. But how did the early believers know whether or not the revelation was true? How could they tell if it was from God, from a false spirit, or from the human spirit? To authenticate the validity of the revelation, God gave the gift of “distinguishing of spirits.” Those having this gift were given the supernatural ability to determine if the revelation was from God or if it was false. John’s exhortation to “test the spirits” has reference to this (1 John 4:1). Similarly, when two or three spoke the revelation of God in the assembly, those having the gift of discerning of spirits were to determine if it was from God (1 Cor. 14:29; cf. 1 Thess. 5:20–21). Because direct revelation has terminated with the completion of the Scriptures, and because the gift of discerning spirits was dependent upon revelation being given, the gift of discerning spirits has ceased.

Showing mercy (Rom. 12:8)

To show mercy (Gk. eleon) means to “feel compassion, show mercy or pity.”[24] In the life of Christ, showing mercy was healing the blind (Matt. 9:27), aiding the Canaanite woman’s daughter (Matt. 15:22), healing an epileptic (Matt. 17:15), and healing the lepers (Luke 17:13). The gift of showing mercy would thus involve showing compassion and help toward the poor, sick, troubled, and suffering people. Moreover, this compassion is to be performed with cheerfulness. The one possessing this gift should perform acts of mercy with gladness, not out of drudgery.

Giving (Rom. 12:8)

The word giving (Gk. metadidous) means “to share with someone;” hence, the gift of giving is the unusual ability and willingness to share one’s material goods with others. The one who has the gift of giving shares his goods eagerly and liberally. The exhortation of Paul is to give “with liberality.” “It refers to open-handed and open-hearted giving out of compassion and a singleness of purpose, not from ambition.”[25] This gift is not reserved for the rich but is for ordinary Christians as well. The Philippians apparently exercised this gift in their giving to Paul (Phil. 4:10–16).

Administration (Rom. 12:8; 1 Cor. 12:28)

In Romans 12:8 Paul refers to the one who leads. This is from the Greek word prohistimi, which means “to stand before,” hence, to lead, rule, or preside. It is used of elders in 1 Thessalonians 5:12 and 1 Timothy 5:17. First Corinthians 12:28 refers to the gift of “administrations” (Gk. kubernesis), literally, “to steer a ship.” Although the above references refer to elders leading the people, the term would probably go beyond that, suggesting also leading in terms of Sunday school superintendent and beyond the local church in ministries such as president or dean of a Christian college or seminary.

Wisdom (1 Cor. 12:8)

The gift of wisdom was important in that it stands first in this list of gifts. Paul explains the gift of wisdom in greater detail in 1 Corinthians 2:6–12 where it is seen to be divinely imparted revelation that Paul could communicate to the believers. Because this gift involved receiving direct revelation, it was a characteristic gift of the apostles who received direct revelation from God.[26] The gift of wisdom thus “is the whole system of revealed truth. One with the gift of wisdom had the capacity to receive this revealed truth from God and present it to the people of God.”[27] Because this gift is related to receiving and transmitting direct revelation from God the gift has ceased with the completion of the canon of Scripture.

Knowledge (1 Cor. 12:8)

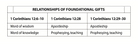

The gift of knowledge appears to be closely related to the gift of wisdom and refers to the ability properly to under stand the truths revealed to the apostles and prophets.[28] This gift relates to the foundational gifts of prophesying and teaching, which would have involved communication of God’s direct revelation to the apostles and prophets (cf. 1 Cor. 12:28). Therefore, this gift too would have ceased with the completion of the Scriptures. First Corinthians 13:8 indicates the cessation of this gift.

The relationship of these gifts is seen in the following diagram:[29]

[1] William McRae, The Dynamics of Spiritual Gifts (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1976), 18.

[2] Charles C. Ryrie, The Holy Spirit (Chicago: Moody, 1965), 83–84.

[3] McRae, Dynamics of Spiritual Gifts, 21.

[4] Pentecost, Divine Comforter, 178; cf. Walvoord, The Holy Spirit, 176.

[5] Thomas R. Edgar, Miraculous Gifts: Are They for Today? (Neptune, N.J.: Loizeaux, 1983), 46–67.

[6] Arndt and Gingrich, Greek-English Lexicon, 723.

[7] See B. B. Warfield, Counterfeit Miracles (Carlisle, Pa.: Banner of Truth, 1918); John F. MacArthur Jr., The Charismatics (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1978), 73–84.

[8] William McRae, The Dynamics of Spiritual Gifts (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1976), 72–73.

[9] Fritz Rienecker, A Linguistic Key to the Greek New Testament, ed. Cleon Rogers (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1980), 429.

[10] McRae, Dynamics of Spiritual Gifts, 69.

[11] Ryrie, The Holy Spirit, 86–87.

[12] It is speculative to suggest that the tongues of Corinthians are angelic languages on the basis of 1 Corinthians 13:1. In that text Paul did not say there actually were angelic languages, nor did he define the gift of tongues as angelic tongues. Instead Paul was supposing a hypothetical situation to emphasize the importance of love.

[13] Leslie B. Flynn, 19 Gifts of the Spirit (Wheaton, Ill.: Victor, 1974), 57

[14] See McRae, Dynamics of Spiritual Gifts, 56–57; and Flynn, in 19 Gifts of the Spirit, 57–61.

[15] Pentecost, Divine Comforter, 173.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Rienecker, Linguistic Key to the Greek New Testament, 430.

[18] A. T. Robertson and Alfred Plummer, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the First Epistle of St. Paul to the Corinthians, in The International Critical Commentary (Edinburgh: Clark, 1914), 281.

[19] McRae, Dynamics of Spiritual Gifts, 66.

[20] See Arthur T. Pierson, George Müller of Bristol (Old Tappan, NJ: Revell, 1971); and Dr. and Mrs. Howard Taylor, Hudson Taylor’s Spiritual Secret (Chicago: Moody, n.d.).

[21] Pentecost, Divine Comforter, 174.

[22] W. E. Vine, The Epistle to the Romans (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1948), 180.

[23] McRae, Dynamics of Spiritual Gifts, 49–50.

[24] H. H. Esser, “Mercy,” in Brown, ed., New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, 2:594.

[25] Rienecker, Linguistic Key to the Greek New Testament, 376.

[26] Charles Hodge, First Corinthians, 245–46.

[27] McRae, Dynamics of Spiritual Gifts, 65.

[28] Hodge, Commentary on the First Epistle to the Corinthians (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1950), 246.

[29] McRae, Dynamics of Spiritual Gifts, 66.

The Moody Handbook of Theology

by Paul Enns

The study of God, His nature, and His Word are all essential to the Christian faith. Now those interested in Christian theology have a newly...

Free ebook: Habits for Spiritual Growth

Sign up for our weekly email and get a free download

Bible Insights by Email

Sign up for learning delivered to your inbox weekly

Free ebook: Habits for Spiritual Growth

Sign up for our weekly email and get a free download